My colleague Stine Arensbach posed a question recently on LinkedIn about the difference between hand-drawn images vs. computer-generated ones and why hand-drawn seemed to her to be more effective. I thought I’d pick up that thread a bit here, since I believe the answers hold implications for both graphic facilitation and graphic communication.

I’ll start by saying that I believe that drawings that are hand-made and loosely or roughly drawn engage us more, drawing us into the process of animating what we’re viewing. By “animating” I mean the way we bring a drawing to life in our mind. Here’s a cartoon from the New Yorker that I’ve shown to graphic facilitation classes I’ve taught over the years:

Reflect for a moment on what happens in our minds when we view this great Gahan Wilson cartoon. We understand the countryside at night. And we understand a school of swimming fish. Because we “know” each of these elements, we can pretend as we look at the cartoon that the scene is real, even though the two could never go together. When we pretend in this way, it’s as if the fish really are swimming through the sky and talking to each other. We animate the scene. In our minds, we bring it to life, imagining it in a way to be true. The absurd juxtaposition makes us laugh, but we only can laugh because, somehow, we can pretend that what we see is real.

So we can think about a drawing being “more effective”, as Stine was asking, when it enables or encourages us to bring it to life in our mind. This isn’t a passive process. It’s a participatory one, where we are deeply engaged. From a facilitator’s point of view, this is a valuable state for people to be in. A facilitator’s work is focused on supporting people to participate, helping them to think actively and collaboratively and tapping their feelings as well. Nothing important gets accomplished if it leaves people flat. Creating new futures begins with imagining them. So having ways to wake up people’s imaginations, even in the simple act of seeing drawings, is important.

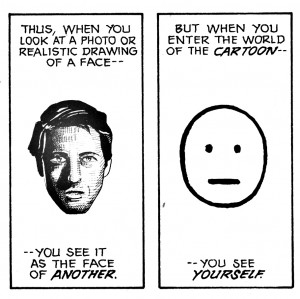

Another thing that allows us to bring Wilson’s cartoon to life is its simplicity, which is to say its abstraction. Scott McCloud, in his amazing book, Understanding Comics, explains how simple, more abstract drawings of people allow us not just to imagine that a drawing is real, but that we are in it:

[This is just a teaser. For McCloud’s full explanation, read his provocative book.] For a facilitator, who is working to build involvement and ownership, the benefits of this phenomenon are obvious.

But why hand-drawn? Pick up an pencil and draw something simple on a piece of paper. Now compare it with a computer-generated drawing or image. The computer’s vector drawing, where the program issues instructions for how and where to create lines and fill in shapes, is perfect. And dead. The lack of variation in a line whose width is always, everywhere exactly the same, leaves us cold. There is nothing there to discover, no variation in tone, width, intensity, shape. Nothing there to wake up our mind, nothing for us to complete or fill in. There’s very little for us to do. Your drawing, in contrast, probably isn’t perfect. Hopefully it’s not only asymmetrical, but varied in tone and line. Even better, it may be simple and incomplete. It will then require your mind to work in order to complete what you’re seeing. (Perhaps you’ll even see yourself there.) Here, then, is something our mind can work on. It has to, since your drawing is varied, moving, unfinished. It’s engaging.

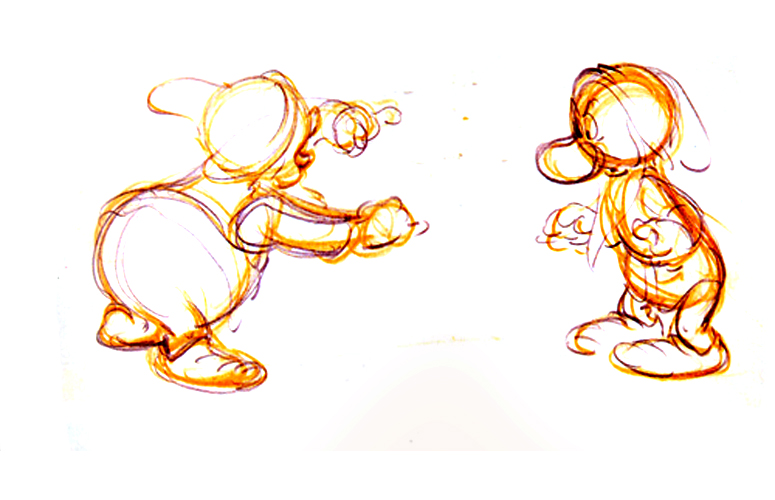

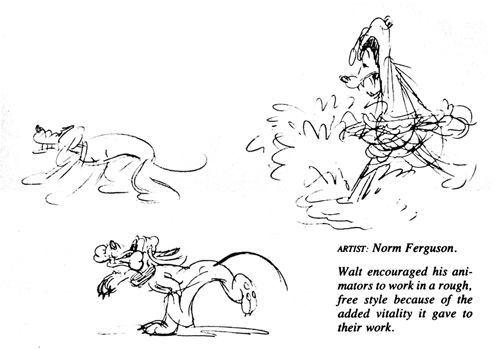

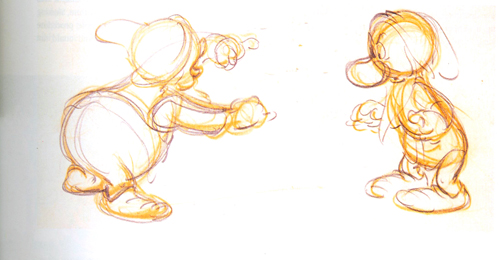

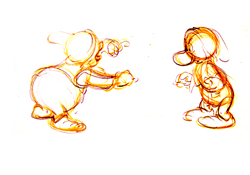

Why rough? Look to the Disney animators of the 1930s. Think for a moment about what they did. They took, at Disney’s constant urging, the young and unformed young medium of animation, and discovered how to create characters that seemed to live, feel and breathe. A marvelous retelling and explanation of how they did this and what they discovered along the way is Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston’s The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation. There were many discoveries that helped them achieve this effect, but one key starting point was this:

Here’s another example, about which Frank and Ollie wrote: Rough drawings open the way to stronger action. As the animator feels the moves in his own body, he transfers that intensity to his character. This type of action could never be achieved with “clean” drawings, but once the roughs have been made refinements can follow.

Again, if it’s life that we want in working with a group, here’s a way to reach for it.

There’s one more thing about rough and hand-drawn that deserves a facilitator’s attention. We can see from the examples above that hand-drawn, lively images engage us as we look at them. I believe that they also send an implicit message that it’s ok to keep working on them. It’s ok to pick up a marker and add something, cross something out, highlight something else. Something hand-drawn and simple says, “This is just a rough sketch, anyway. There’s still room to perfect it. Join in.” A highly polished graphic, on the other hand, says, “This has been completely worked out and it’s ready for you to consider. Do you like it or not?” One is an invitation to participate, the other is a presentation.

So, why rough, simple, hand-drawn? It’s more alive, more engaging and more inviting. When you’re working with groups who are thinking, planning, imagining, creating, that’s just what you want.

[…] enough, a couple of days later I stumbled across an interesting piece that validates this. In Rough and Hand-drawn: Alive and Inviting Tom Benthin talks about how, when compared to computer created images, “more abstract […]

[…] enough, a couple of days later I stumbled across an interesting piece that validates this. In Rough and Hand-drawn: Alive and Inviting Tom Benthin talks about how, when compared to computer created images, “more abstract […]